At the Crossroads of Crisis: Why the G20 Johannesburg in Johannesburg Was a Crucial Test of Global Co-operation

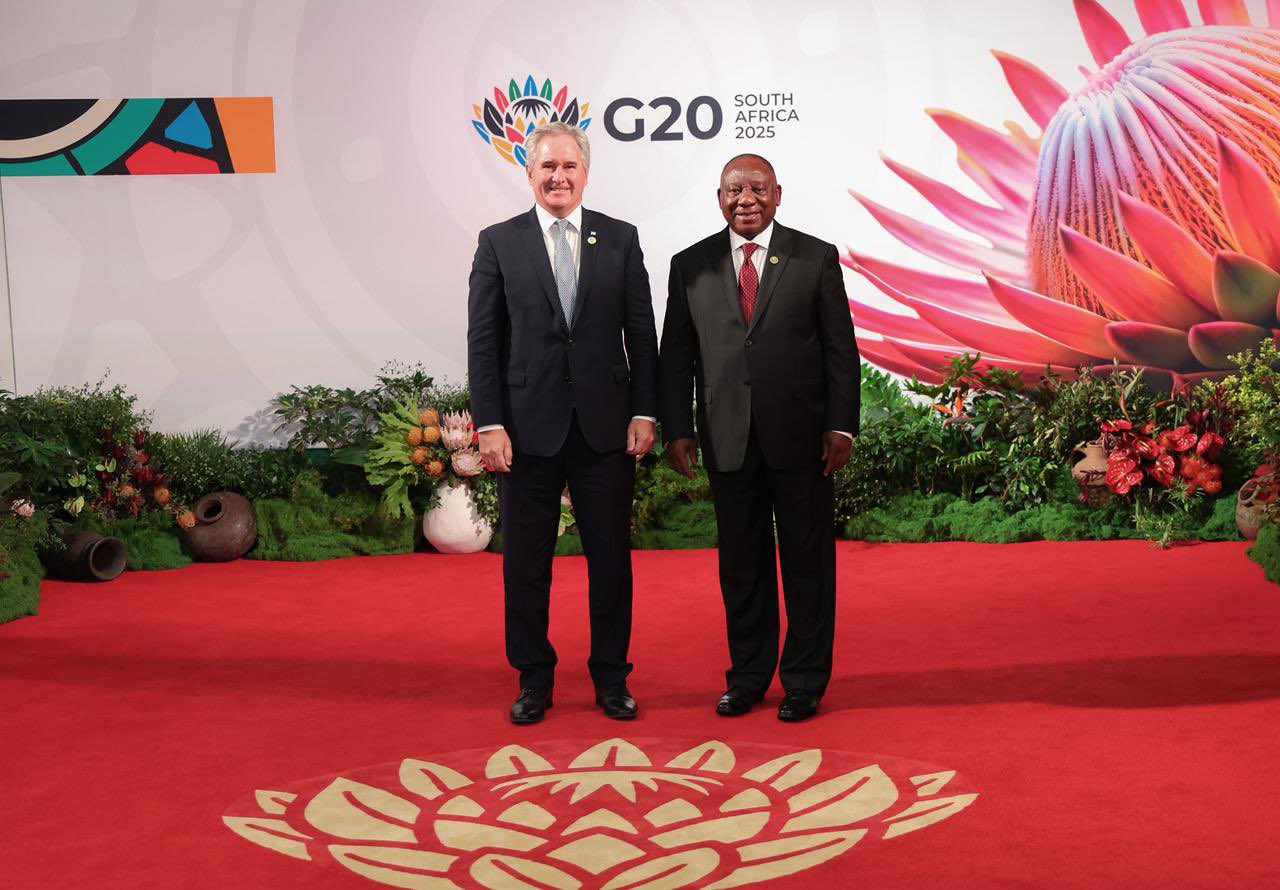

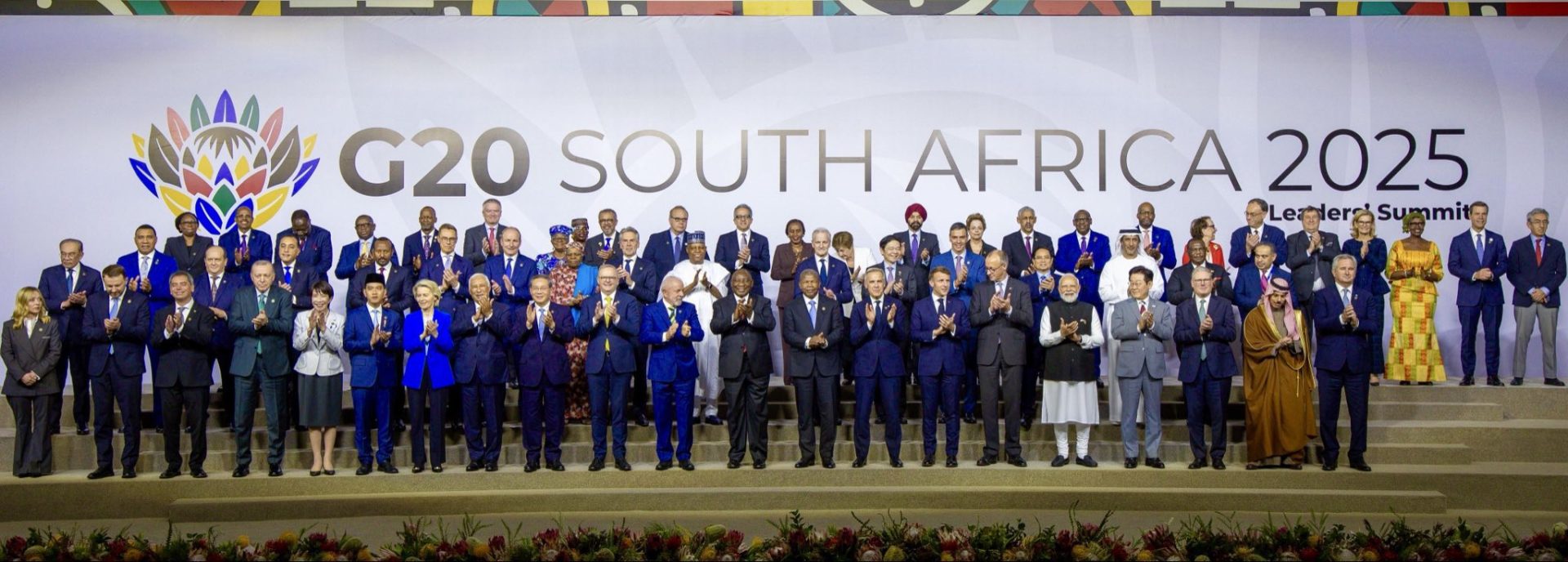

JOHANNESBURG — The world watched with bated breath as global leaders descended upon Johannesburg, the air thick not only with the promise of diplomacy but with a palpable sense of existential reckoning. This was not just another gathering of the G20; it was the first ever hosted on African soil, set against a backdrop of war, economic fragility, and a climate in crisis. More than a policy forum, the summit became a litmus test for multilateralism itself. Could this premier economic council, forged in the fires of the 2008 financial crash, prove its relevance in an era of profound fragmentation?

The G20 Summit in Johannesburg convened at a critical juncture for global co-operation, its relevance hanging in the balance amidst a turbulent backdrop of geopolitical strife, economic instability, and a deepening climate crisis. Hosted for the first time on the African continent, the summit was more than a meeting; it was a crucial test of multilateralism’s ability to deliver in an age of fragmentation. Under South Africa’s strategic presidency, the proceedings were dominated by an urgent mission to protect and fortify the G20’s credibility, steering its focus squarely towards the needs of the developing world.

This in-depth analysis explores the summit’s pivotal outcomes, from the landmark adoption of African industrialisation as a core priority to the creation of the groundbreaking Africa Investment Atlas—a digital lifeline scheduled for launch in February 2025 designed to demystify the continent’s investment landscape. We examine the twenty key pillars of the new global consensus, including the imperative to boost food production, build resilient health systems, and tackle the vicious cycle of poverty and conflict. While the summit concluded with a verdict of cautious hope, acknowledging the arduous consensus conundrum and the difficult trade-offs between growth and sustainability, its legacy will ultimately be judged by the translation of shared responsibility into tangible shared prosperity. Join us as we unpack how Johannesburg became a crossroads for a generation, aiming to build a system where no person, community, or continent is left behind.

This in-depth analysis explores the summit’s pivotal outcomes, from the landmark adoption of African industrialisation as a core priority to the creation of the groundbreaking Africa Investment Atlas—a digital lifeline scheduled for launch in February 2025 designed to demystify the continent’s investment landscape. We examine the twenty key pillars of the new global consensus, including the imperative to boost food production, build resilient health systems, and tackle the vicious cycle of poverty and conflict. While the summit concluded with a verdict of cautious hope, acknowledging the arduous consensus conundrum and the difficult trade-offs between growth and sustainability, its legacy will ultimately be judged by the translation of shared responsibility into tangible shared prosperity. Join us as we unpack how Johannesburg became a crossroads for a generation, aiming to build a system where no person, community, or continent is left behind.

The Twenty Pillars of a New Global Consensus

The discussions in Sandton’s conference halls hammered home a sobering truth: a perfect storm of interlocking crises now jeopardises our collective future. The summit coalesced around a renewed global strategy, articulated through twenty interconnected priorities:

-

A Critical Juncture for Multilateralism: The G20’s Moment of Reckoning in Johannesburg

The assertion that the G20 Summit in Johannesburg convened at a “critical juncture for multilateralism” is not merely diplomatic rhetoric; it was the foundational reality upon which every discussion was built. To understand the profound significance of this meeting, one must appreciate the perfect storm of geopolitical and institutional pressures that defined the moment, all set against the symbolic backdrop of the African continent—a region with a deep and complex relationship with the global order.

The Unravelling of the Post-War Fabric

The post-Second World War system, painstakingly constructed around institutions like the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank, was designed to foster co-operation, prevent conflict, and manage global crises through collective action. However, in Johannesburg, leaders were forced to openly acknowledge that this fabric is fraying, if not unravelling. The causes are manifold:

-

Geopolitical Rivalry: The escalating tensions between major powers, particularly the West on one side and a resurgent Russia and China on the other, have paralysed institutions like the UN Security Council. The war in Ukraine served as a stark, bloody testament to the failure of this system to keep the peace or hold aggressors to account.

-

Institutional Rigidity: Many of these 20th-century institutions are seen as anachronistic, reflecting a global power balance that no longer exists. The clamour for reform—such as restructuring the UN Security Council to include permanent representation for powers like India or a unified African voice—grows ever louder, yet the path to change is blocked by entrenched interests.

-

The Erosion of Trust: A rising tide of nationalism and protectionism in many leading economies has directly undermined the spirit of multilateralism. The default position is shifting from “what can we achieve together?” to “what must I protect for myself?”

Why Africa was the Perfect, and Imperfect, Host

The choice of South Africa as the host nation was both poignant and politically charged. Africa has often been on the sharp end of a multilateral system that has, at times, failed to deliver. It has borne the brunt of climate change it did not cause, economic instability dictated by distant markets, and security crises that outpace international response. Therefore, for the G20 to meet in Johannesburg was to bring its crisis of credibility to the very doorstep of those who have the most to lose from its collapse.

This setting forced an uncomfortable but necessary introspection. It was a living reminder that for multilateralism to have any relevance in the 21st century, it must evolve beyond a club of established powers and become truly representative. The very legitimacy of the forum was being judged by its ability to address the pressing issues of the host continent—from debt distress to energy access and equitable growth.

This setting forced an uncomfortable but necessary introspection. It was a living reminder that for multilateralism to have any relevance in the 21st century, it must evolve beyond a club of established powers and become truly representative. The very legitimacy of the forum was being judged by its ability to address the pressing issues of the host continent—from debt distress to energy access and equitable growth.The Adage and the Imperative

In this context, the old adage, “a stitch in time saves nine,” feels profoundly apt. The G20 members arrived in Johannesburg facing a choice. They could continue to apply temporary, piecemeal fixes to the symptoms of a broken system—managing each migration crisis, debt default, or trade dispute in isolation. Or, they could attempt the more difficult, foundational work of repairing the very fabric of global governance before the tears became irreparable.

The “critical juncture” was this precise fork in the road. Allowing the integrity of the G20 to weaken further would be to ignore the loose threads, guaranteeing a much larger, more complex, and costly unravelling later. The collective responsibility “not to allow the integrity and the credibility of the G20 to be weakened,” which became a recurrent theme of the summit, was a direct acknowledgement of this adage’s wisdom. The leaders understood that preventative, co-operative maintenance of the global system in Johannesburg was imperative to avoid a catastrophic, and far more expensive, rebuild in the future.

Conclusion: A Test Passed, But Just Barely

The Johannesburg summit did not magically resolve the deep-seated crises of multilateralism. It did, however, represent a crucial first “stitch.” By simply convening successfully, by focusing on African development as a core global priority, and by launching tangible tools like the Africa Investment Atlas, the G20 demonstrated a will to survive. It proved that even in an age of fragmentation, the forum remains one of the few tables large enough to host the world’s most difficult conversations. The meeting in Johannesburg was not the completion of the repair job, but it was a vital, and long-overdue, start.

-

-

Credibility as the Core Mission: The G20’s Fight for Relevance in Johannesburg

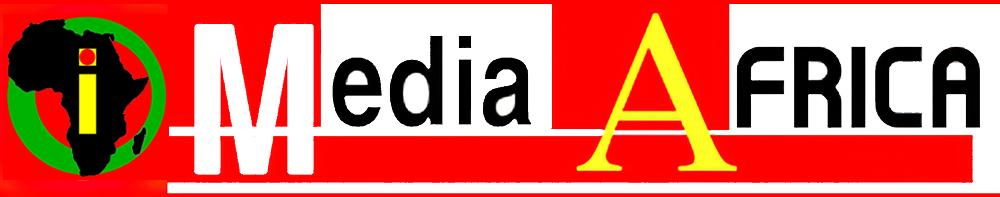

To describe “credibility as the core mission” of the Johannesburg summit is to identify the central, urgent struggle that defined the entire gathering. This was not merely one agenda item among many; it was the overriding objective that underpinned every negotiation, every handshake, and every line of the final communiqué. In essence, the G20 was not just discussing global policy—it was fighting for its own survival and relevance as the premier forum for international economic co-operation.

The Credibility Deficit

Prior to the summit, the G20 was suffering from a profound credibility deficit. The world had grown weary of seeing its summits devolve into stages for geopolitical grandstanding, producing lofty declarations that often withered in the face of national self-interest. The group, conceived in the crucible of the 2008 financial crisis to provide swift, unified global action, was now seen as paralysed by the very divisions it was meant to transcend. The war in Ukraine, and the differing allegiances it exposed within the G20, had brought this paralysis into sharp relief. The forum risked becoming a talking shop—all pomp and no consequence.

Why the African Setting was a Litmus Test

Holding the summit in South Africa transformed this abstract crisis of credibility into a tangible test. Africa, more than any other region, has a historical sensitivity to the gap between international promises and delivered outcomes. For the host nation and its continental peers, the G20’s credibility was not an academic question; it was a matter of practical necessity. Would this meeting be another instance of the global North dictating terms to the global South, or would it signal a genuine shift towards equitable partnership?

The very integrity of the G20 was therefore on trial. If it could not deliver meaningful outcomes for its host continent—if it descended into acrimony and produced another anodyne, lowest-common-denominator statement—it would prove its own irrelevance. The credibility South Africa sought to fortify was twofold: the G20’s internal credibility as a functional body capable of agreement, and its external credibility according to a sceptical world, particularly the developing nations watching closely from the sidelines.

The very integrity of the G20 was therefore on trial. If it could not deliver meaningful outcomes for its host continent—if it descended into acrimony and produced another anodyne, lowest-common-denominator statement—it would prove its own irrelevance. The credibility South Africa sought to fortify was twofold: the G20’s internal credibility as a functional body capable of agreement, and its external credibility according to a sceptical world, particularly the developing nations watching closely from the sidelines.The Adage and the Action

In this endeavour, the old adage, “the proof of the pudding is in the eating,” became the unspoken benchmark for success. The South African presidency understood that the G20 could no longer survive on the recipe alone—the elegant texts and well-meaning pledges. The world needed to taste the pudding. It needed to see concrete, actionable outcomes that translated diplomatic consensus into tangible progress on the ground.

This focus on delivering “proof” is what shaped the summit’s most significant achievements. The commitment to the Africa Investment Atlas, with its clear February 2025 launch date and transparent framework for tracking capital, was a deliberate move to provide a measurable, concrete outcome. It was designed to be a tool whose utility could be assessed and whose impact could be tracked. Similarly, the forceful push for continental industrialisation and the explicit mandate to “increase food production” were responses to long-standing African priorities. They were specific, understandable, and, crucially, their success or failure would be evident in the years to come.

Moving Beyond Divisive Politics

Fortifying credibility necessitated a conscious, and often delicate, effort to steer the conversation away from the most polarising geopolitical fissures and towards common ground. This did not mean ignoring conflict or injustice, but rather framing discussions around shared challenges where co-operation was not just possible but essential. Climate change, pandemic preparedness, and sustainable development are issues that respect no borders and impact every nation in the room, albeit unequally. By focusing on these intersectional crises, the South African presidency worked to build bridges between the G7, the BRICS nations, and the Global South, demonstrating that the forum could still be a venue for pragmatic problem-solving, even among adversaries.

Conclusion: A Mission Temporarily Accomplished

The mission to protect and fortify the G20’s credibility in Johannesburg was, by the measure of the outcome, a qualified success. The summit did not collapse into disarray. It produced a consensus declaration and launched initiatives with genuine potential. By choosing to “eat the pudding” rather than just admire the recipe, the G20 took a vital step towards restoring its stature.

However, credibility is a currency that is earned in increments and can be spent in a moment. The Johannesburg summit stopped the bleeding and applied a crucial stitch, but the patient is not yet fully recovered. The true test of this renewed credibility will be the implementation of the promises made—the timely launch of the Atlas, the tangible flow of investment, and the visible progress on industrialisation. The core mission was achieved for now, but the vigilance to maintain that hard-won credibility is the enduring challenge that remains.

However, credibility is a currency that is earned in increments and can be spent in a moment. The Johannesburg summit stopped the bleeding and applied a crucial stitch, but the patient is not yet fully recovered. The true test of this renewed credibility will be the implementation of the promises made—the timely launch of the Atlas, the tangible flow of investment, and the visible progress on industrialisation. The core mission was achieved for now, but the vigilance to maintain that hard-won credibility is the enduring challenge that remains. -

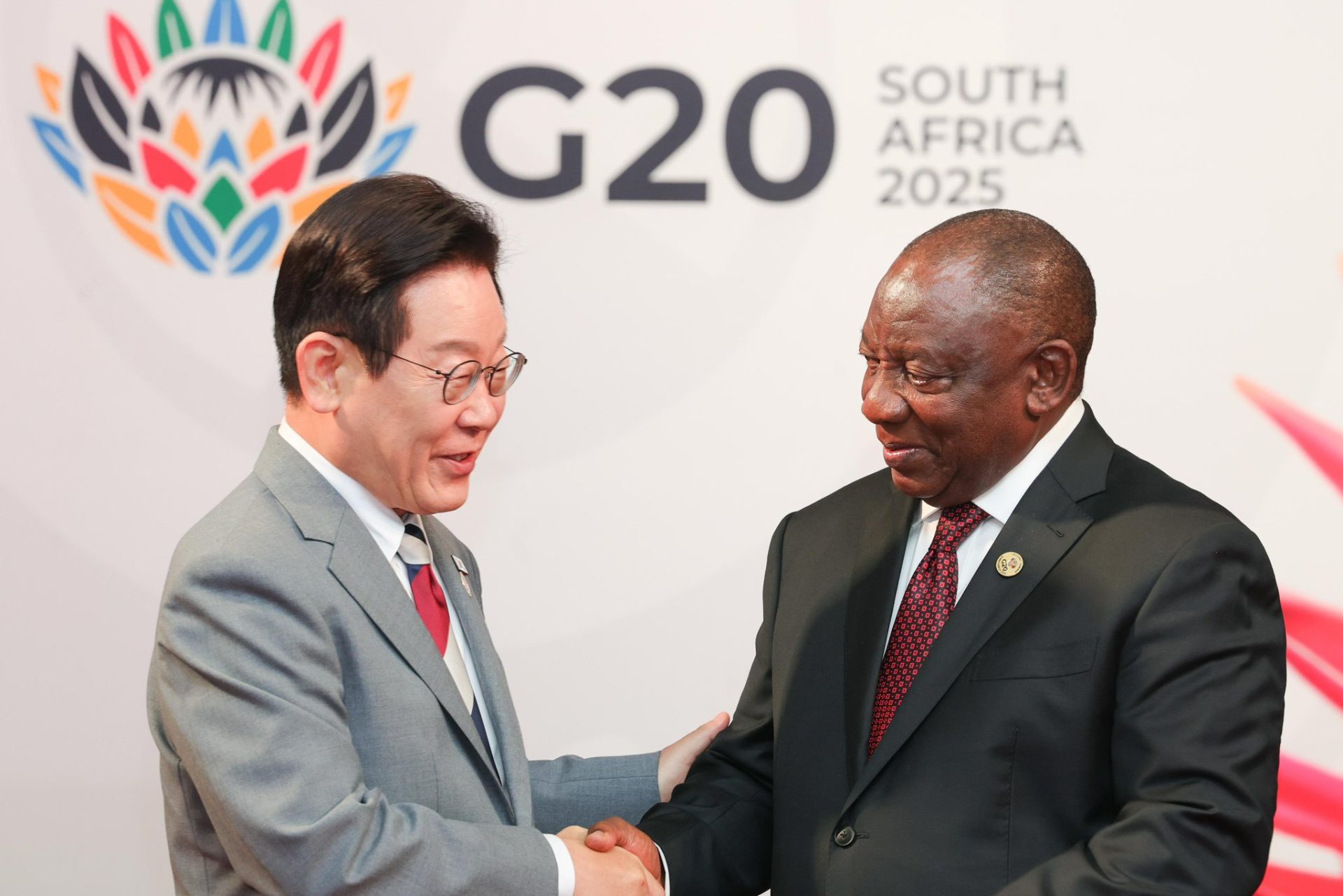

The African Pivot: How Johannesburg Forced the World to Recalibrate

The decision for South Africa to host the G20 Leaders’ Summit was far more than a rotational honour or a mere talking point; it was a strategic masterstroke that fundamentally altered the forum’s perspective. This “African Pivot” was not merely about geography, but about a profound and necessary recalibration of global priorities. For the first time, the world’s premier economic council was not discussing Africa from a distant, theoretical podium—it was embedded within its vibrant, complex, and urgent reality.

The Historical Context: A Continent on the Periphery

Historically, Africa has often been relegated to the sidelines of such high-level global economic governance. It was frequently a subject on the agenda, not a shaper of it. Discussions were too often framed through a lens of deficit—a continent in need of aid, debt relief, or crisis management. While these challenges are real, this narrative overshadowed the immense opportunities and the fundamental truth that global challenges cannot be solved without Africa, not merely for it. The continent is home to the world’s youngest and fastest-growing population, vast renewable and mineral resources critical for the green transition, and a burgeoning digital economy. To ignore this was not just shortsighted; it was a strategic blind spot for the G20.

The Strategic Masterstroke of Location

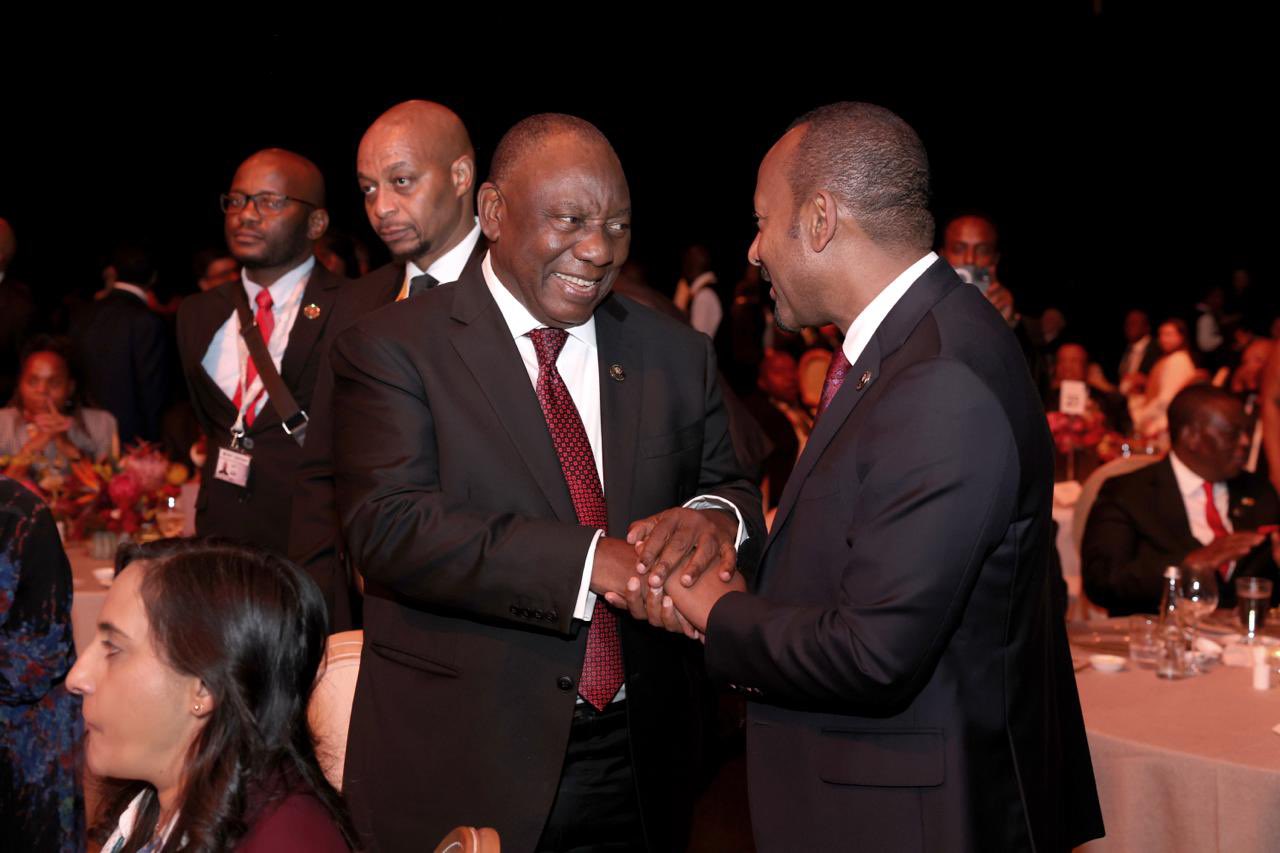

By placing the summit in the heart of Johannesburg, the South African presidency engineered a powerful, inescapable context. Leaders were not insulated in a remote conference centre; they were surrounded by the palpable energy, challenges, and ambitions of the African century. The venue itself became a constant, silent delegate in every meeting. It forced a structural focus because the evidence was all around them: the need for infrastructure investment, the potential of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), and the stark realities of climate vulnerability.

This physical presence made abstract issues concrete. Discussing food security is one thing; doing so while being reminded of the drought gripping the Horn of Africa is another. Debating energy transitions takes on new meaning when your host nation is grappling with the complex justice of moving from coal to renewables while ensuring energy access for its people. The summit was, in effect, an immersion course for global leaders on 21st-century realities.

This physical presence made abstract issues concrete. Discussing food security is one thing; doing so while being reminded of the drought gripping the Horn of Africa is another. Debating energy transitions takes on new meaning when your host nation is grappling with the complex justice of moving from coal to renewables while ensuring energy access for its people. The summit was, in effect, an immersion course for global leaders on 21st-century realities.The Adage and the Shift in Perspective

This pivot aligns perfectly with the adage, “out of sight, out of mind.” For too long, despite its size and potential, Africa had been functionally “out of sight” for the concentrated power brokers of the G20. Its specific needs—such as building manufacturing capacity, not just exporting raw materials, or developing climate-resilient agriculture—were often secondary to the immediate concerns of advanced economies.

The Johannesburg summit dragged Africa firmly and irrevocably back into the centre of the global mind. It made the continent’s challenges and opportunities impossible to ignore. By doing so, it challenged the very structure of the G20’s thinking. The discussions were no longer about how to help Africa, but about how to partner with it for mutual gain. Initiatives like the Africa Investment Atlas and the focus on continental industrialisation are direct results of this shifted perspective. They are designed not as charitable gestures, but as mechanisms for smart, transparent investment in the world’s next great growth market.

The Lasting Impact of the Pivot

The true success of the African Pivot will be measured by its legacy. Did it create a permanent shift in the G20’s agenda? The elevation of the African Union to a permanent member of the G20 is the most tangible testament to its success, a direct outcome of the momentum generated by South Africa’s presidency. This move ensures that Africa will now have a permanent, seated voice at the table, transforming the G20’s structure to better reflect global realities.

Furthermore, it has set a new benchmark for future summits. The bar has been raised; mere rhetorical nods to “developing nations” will no longer suffice. The Johannesburg meeting demonstrated that the most pressing global issues—from climate adaptation and future pandemic preparedness to economic stability—are inextricably linked to Africa’s fate. To fail there is to fail globally.

In conclusion, the African Pivot was a necessary intervention in a stale and increasingly irrelevant dialogue. By forcing a structural focus on the continent, South Africa did not just host a summit; it curated a crucial intervention, ensuring that the world could no longer afford to keep Africa “out of sight and out of mind.” The G20 left Johannesburg with a clear, inescapable understanding: the path to global resilience and prosperity in this century runs directly through the African continent.

In conclusion, the African Pivot was a necessary intervention in a stale and increasingly irrelevant dialogue. By forcing a structural focus on the continent, South Africa did not just host a summit; it curated a crucial intervention, ensuring that the world could no longer afford to keep Africa “out of sight and out of mind.” The G20 left Johannesburg with a clear, inescapable understanding: the path to global resilience and prosperity in this century runs directly through the African continent. -

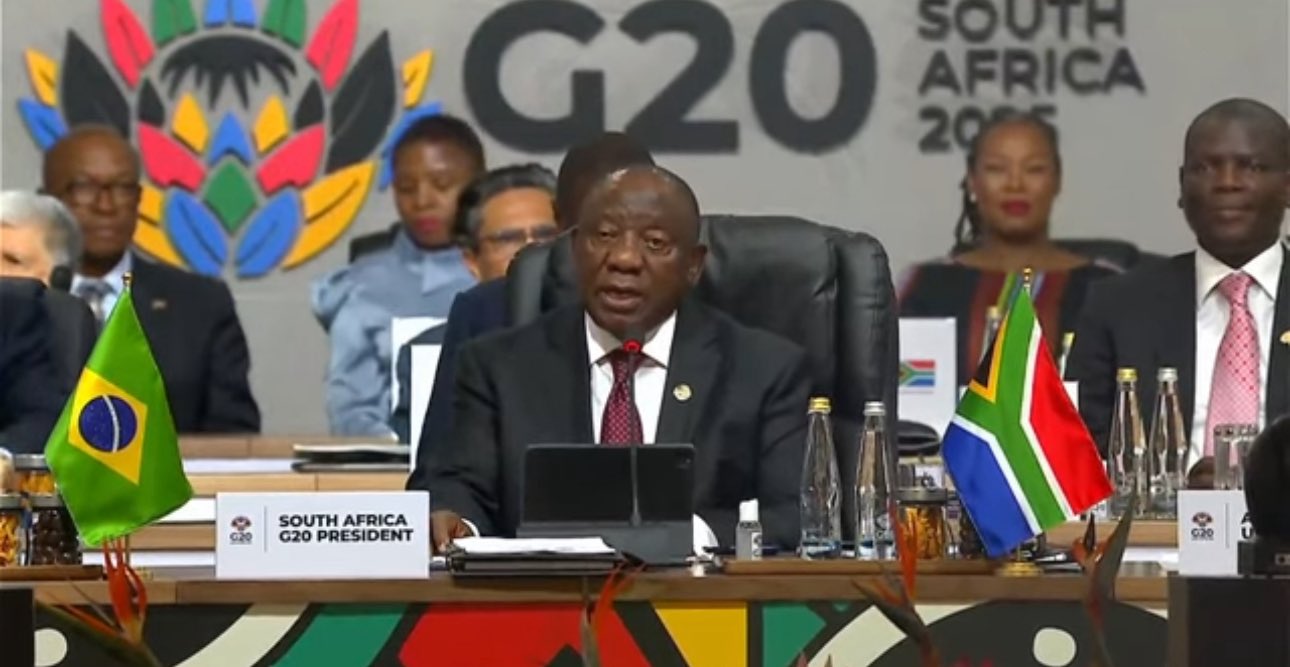

Founding Principles Reaffirmed: How Johannesburg Returned the G20 to its Roots

In the bustling halls of the Sandton Convention Centre, amidst the complex geopolitics of the 21st century, a powerful and deliberate echo from the past could be heard. South Africa, as host, chose a theme that was both a conscious recall and a necessary corrective: a return to the G20’s original, founding mission—delivering global economic stability through co-operative action, not isolation. This was not merely nostalgic rhetoric; it was a strategic reclamation of the forum’s very reason for being, delivered from a continent that understands the catastrophic cost of economic fragmentation.

The 2008 Crucible: A Lesson in Unity

To appreciate the significance of this reaffirmation, one must first recall the G20’s genesis. It was born in the white-hot crisis of the 2008 global financial meltdown. As the world’s economies teetered on the brink, the existing G7 framework was revealed as insufficient. In a moment of collective clarity, established and emerging powers—including South Africa—came together in an unprecedented display of unity. They recognised that in a globalised economy, a crisis in one market was a crisis in all. The solution was not for nations to retreat behind protectionist walls, but to co-ordinate stimulus packages, regulate financial markets, and inject liquidity through bodies like the IMF. Their co-operative action, quite literally, pulled the world back from the economic abyss.

The Drift Towards Isolation

In the years that followed, however, that hard-won spirit of co-operation began to fray. The rise of nationalist and populist movements in major economies, the bitter trade wars, the devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic which exposed “vaccine nationalism,” and the return of armed conflict in Europe—all these factors fostered a retreat towards zero-sum thinking and isolationist policies. The G20 risked becoming a mirror to these divisions, a stage where geopolitical rivalries were performed rather than resolved.

The African Host as the Perfect Arbiter

It was in this context of fragmentation that South Africa’s role became pivotal. Africa, perhaps more than any other region, suffers acutely when global co-operation fails. It bears the brunt of inflation driven by distant wars, climate change it did not create, and capital flight triggered by volatility in other markets. Conversely, it stands to gain immensely when co-operation succeeds—through equitable trade, stable investment, and shared technology.

Therefore, the host nation was uniquely positioned to remind the G20 of its original purpose. From Africa’s perspective, the choice is stark: a world of isolation is a world of perpetual catch-up and vulnerability. A world of co-operation is one of shared stability and growth. By framing the agenda around this core principle, South Africa masterfully shifted the focus from what divides the great powers to what unites all nations: the fundamental need for a stable, predictable, and inclusive global economic order.

Therefore, the host nation was uniquely positioned to remind the G20 of its original purpose. From Africa’s perspective, the choice is stark: a world of isolation is a world of perpetual catch-up and vulnerability. A world of co-operation is one of shared stability and growth. By framing the agenda around this core principle, South Africa masterfully shifted the focus from what divides the great powers to what unites all nations: the fundamental need for a stable, predictable, and inclusive global economic order.The Adage and the Imperative

This reaffirmation of first principles brings to mind the timeless adage, “united we stand, divided we fall.” The G20 in 2008 understood this intimately; their unity was their strength. The drift towards isolation was a forgetfulness of this basic truth, a gamble that any nation, no matter how powerful, can thrive in a destabilised world.

The Johannesburg summit served as a powerful, necessary reminder of the adage’s wisdom. The “convergence of crises” cited by leaders—from climate and health to food and energy insecurity—are global problems with no unilateral solutions. One nation building higher walls will not stop a pandemic or reverse global warming. One bloc hoarding resources will not stabilise the global food supply. The only logical path forward is the one first charted in 2008: co-operative action.

From Principle to Practice in Johannesburg

This was not merely a philosophical exercise. The reaffirmation of this founding principle was made tangible through the summit’s outcomes. The commitment to the Africa Investment Atlas is a prime example. It is a tool built on the logic of connection and transparency, designed to de-risk investment and channel capital towards sustainable development—a direct antidote to the uncertainty that isolationism breeds. Similarly, the collective focus on food production and energy stability for vulnerable nations acknowledges that our economic fates are intertwined; preventing famine and state collapse elsewhere is an investment in one’s own long-term security and economic stability.

In conclusion, by using its presidency to reaffirm the founding mission of co-operative action, South Africa performed a vital service for the G20 and the world. It reminded the forum that its credibility and utility do not lie in navigating divisions, but in transcending them. The summit in Johannesburg was a potent declaration that in the face of polycrisis, the childish allure of isolation must be abandoned for the mature, proven wisdom of collaboration. For, as the adage warns, a divided house—especially a global one—cannot hope to stand.

In conclusion, by using its presidency to reaffirm the founding mission of co-operative action, South Africa performed a vital service for the G20 and the world. It reminded the forum that its credibility and utility do not lie in navigating divisions, but in transcending them. The summit in Johannesburg was a potent declaration that in the face of polycrisis, the childish allure of isolation must be abandoned for the mature, proven wisdom of collaboration. For, as the adage warns, a divided house—especially a global one—cannot hope to stand. -

The Crisis Convergence: Why the G20 Finally Acknowledged the Perfect Storm

In the rarefied air of global diplomacy, it is often politically convenient to treat the world’s ailments as separate maladies, each with its own specialist and prescription. The groundbreaking achievement of the Johannesburg summit was its formal, collective acknowledgement that this approach is now obsolete. Leaders stood before a stark new reality: climate change, pandemics, and economic instability are no longer isolated issues operating in parallel; they have converged into a single, self-reinforcing threat, a “polycrisis” that demands a holistic, integrated response. This recognition fundamentally changes the mandate of global co-operation.

The Anatomy of a Convergent Threat

To understand the gravity of this shift, one must see how these crises feed into one another, creating a vicious cycle that is greater than the sum of its parts. The African context provides the most vivid illustration of this convergence:

-

Climate Change Fuels Economic and Health Crises: Consider a severe drought in the Horn of Africa, exacerbated by climate change. It decimates agricultural yields (an economic shock to farmers and national GDP), leading to food scarcity and malnutrition (a public health crisis). This malnutrition weakens populations, making them more susceptible to diseases (a further strain on health systems), while governments are forced to spend scarce resources on food imports and medical aid, diverting funds from long-term development and creating debt distress (a fiscal crisis).

-

Pandemics Exacerbate Economic and Climate Vulnerabilities: The COVID-19 pandemic was a brutal lesson in convergence. Lockdowns shattered supply chains and halted tourism (economic instability), which in turn reduced funding for climate adaptation projects. Furthermore, the scramble for vaccines exposed deep global inequalities, undermining trust in multilateral systems precisely when co-operation was most needed to manage the economic fallout.

-

Economic Instability Undermines Climate and Health Resilience: A country facing debt distress and currency devaluation cannot invest in renewable energy infrastructure or robust public health systems. It becomes more vulnerable to the next climate shock or disease outbreak, locking it into a downward spiral of reaction and recovery, with no capacity for prevention or building long-term resilience.

The G20’s Paradigm Shift in Johannesburg

Prior to this summit, the G20’s working groups often operated in silos: finance ministers discussed macroeconomic policy, energy ministers discussed transition, and health ministers discussed pandemic preparedness. The “Crisis Convergence” concept shatters these silos. The South African presidency, drawing on the continent’s direct experience of these intertwined shocks, forced the forum to see the connections.

The formal recognition of this convergence means that it is no longer sufficient to have a climate plan, a separate health strategy, and an isolated economic framework. A climate plan that doesn’t consider food security is flawed. An economic recovery plan that ignores a nation’s vulnerability to future pandemics is built on sand. A health initiative that isn’t funded through stable and sustainable economic policies will collapse.

The Adage and the Imperative

This new reality calls to mind the timeless adage, “a chain is no stronger than its weakest link.” For decades, the global community has tried to strengthen individual links—bolstering financial systems here, funding climate research there. But the convergent nature of today’s threats means that the entire chain of global stability is now exposed to the fragility of its most vulnerable points.

A health crisis in one region can snap the link of global supply chains, which in turn strains economic stability worldwide. A climate-induced famine can snap the link of social order, triggering migration and political instability that reverberates across continents. The G20, representing the world’s largest economies, finally acknowledged in Johannesburg that their own security and prosperity are inextricably tied to the strength of the weakest links in the global chain—often found in developing nations, particularly in Africa.

A health crisis in one region can snap the link of global supply chains, which in turn strains economic stability worldwide. A climate-induced famine can snap the link of social order, triggering migration and political instability that reverberates across continents. The G20, representing the world’s largest economies, finally acknowledged in Johannesburg that their own security and prosperity are inextricably tied to the strength of the weakest links in the global chain—often found in developing nations, particularly in Africa.From Recognition to Holistic Response

This acknowledgement moves the G20 from a reactive to a proactive posture. The initiatives launched in Johannesburg, such as the Africa Investment Atlas, must now be viewed through this convergent lens. The Atlas is not merely an economic tool; it is a instrument for building comprehensive resilience. By directing transparent investment towards climate-resilient infrastructure, sustainable agriculture, and robust healthcare systems, it simultaneously strengthens multiple links in the chain.

Similarly, the focus on boosting food production is not just about economics; it is a climate adaptation and health security measure. The push for local vaccine manufacturing in Africa is not just a health policy; it is an industrial strategy that builds economic capacity and strategic autonomy.

In conclusion, the formal recognition of the Crisis Convergence in Johannesburg was one of the summit’s most significant outcomes. It marks a maturation in global governance, an understanding that the neat categorisations of the past are a dangerous fiction. The world can no longer afford to have climate diplomats, health officials, and finance ministers working in separate rooms. They must now sit at the same table, because the crises they face are already in the same room, feeding off one another. The G20 has rightly identified the problem; its enduring challenge is to forge the fully integrated, holistic solutions that this perfect storm demands.

-

-

The Geopolitical Drag: How the Shadow of War Weighed Heavy on Johannesburg’s Summit

Amidst the ambitious agenda of the Johannesburg G20 summit, a persistent and divisive spectre loomed over the proceedings: the war in Ukraine. This was not merely a distant conflict on another continent, but a palpable force acting as a primary impediment to progress. Termed here as the “Geopolitical Drag,” this phenomenon describes the way in which escalating geopolitical tensions create a powerful, countervailing force that directly undermines the spirit of global co-operation, sapping momentum, complicating consensus, and threatening to derail the entire multilateral project.

The Uninvited Guest at the Table

The G20 was conceived as a forum for macroeconomic co-ordination, a place where finance ministers and leaders could discuss shared economic challenges irrespective of political differences. The war in Ukraine fundamentally violated this premise. It forced a security and moral crisis onto an economic agenda, creating an inescapable fault line between the Western nations (the G7 and their allies) and the Russia-China axis, with many “Global South” nations, including key African powers, caught in the middle.

In Johannesburg, this drag manifested in several ways:

-

The Poisoning of Diplomacy: Trust, the essential currency of negotiation, was in short supply. Every proposal, whether on climate finance or debt relief, was viewed through a new, cynical lens of geopolitical alignment. Was a nation’s position on food security a genuine concern, or a proxy for its stance on the war? This underlying suspicion made building the necessary consensus for bold action incredibly arduous.

-

The Diversion of Resources and Attention: The conflict has triggered a massive reallocation of financial and political capital in Western nations towards military aid and supporting Ukraine. This inevitably diminishes the resources and focus available for long-term global challenges like climate finance or development aid in Africa. The very funds needed to implement the G20’s ambitions are being diverted to address a immediate geopolitical fire.

-

The Weaponisation of Interdependence: The war has demonstrated how global economic interconnections—in energy, food, and finance—can be weaponised. The resultant sanctions and counter-sanctions have shattered the notion of a neutral global economic space, forcing every nation to recalculate its economic relationships based on political risk, not just market efficiency.

The African Dilemma: A Continent in the Crossfire

For the African hosts and delegates, this Geopolitical Drag was particularly acute and frustrating. The continent has historically been a theatre for proxy conflicts and its nations have no desire to be forced into a new binary alignment. Their primary concerns are domestic and continental: economic development, climate adaptation, and poverty alleviation.

From an African perspective, the constant refocusing on the Ukraine war felt like a distraction from the summit’s core purpose. The adage that perfectly captures this sentiment is, “When elephants fight, the grass suffers.” In this scenario, the great powers—the East and West—are the elephants. Africa, along with other developing regions, is the grass, being trampled underfoot by a conflict not of its making. The war’s secondary effects—soaring food and fertiliser prices, financial volatility, and inflationary pressures—are causing immense suffering on the continent, undermining the very stability the G20 was meant to foster.

The South African Balancing Act

South Africa, as host, faced an immense challenge: how to navigate this drag without allowing the summit to collapse. Its much-discussed “non-aligned” stance, while criticised by some Western powers, was a pragmatic necessity to keep all parties at the table. The host’s objective was to prevent the Ukraine conflict from becoming the only agenda item, thereby allowing space for discussions on the African Investment Atlas, climate finance, and health security to proceed.

The final communiqué’s language on Ukraine—often the most heavily negotiated section—was a testament to this difficult balancing act. Any wording was a compromise, reflecting the deep divisions and the sheer effort required to achieve even a fragile consensus on the topic, effort that could have been channeled into more constructive co-operation.

Conclusion: The Enduring Impediment

The Geopolitical Drag identified in Johannesburg is not a temporary inconvenience; it is a structural weakness in the contemporary global order. The summit proved that while there is a shared recognition of convergent crises like climate and health, the political will to co-operate on solutions is being systematically undermined by great-power rivalry.

Ultimately, the G20 found a way to survive the drag, but not to overcome it. It managed to produce outcomes despite the tensions, a credit to the diplomatic skill of the South African presidency. However, the experience served as a stark warning: for the G20 to truly fortify its credibility and deliver on its promises, it must find a way to insulate critical global economic co-operation from the corrosive effects of geopolitical conflict. Failing to do so ensures that the “elephants” will continue to fight, and the “grass”—the prospects for sustainable development and shared prosperity—will continue to suffer.

Ultimately, the G20 found a way to survive the drag, but not to overcome it. It managed to produce outcomes despite the tensions, a credit to the diplomatic skill of the South African presidency. However, the experience served as a stark warning: for the G20 to truly fortify its credibility and deliver on its promises, it must find a way to insulate critical global economic co-operation from the corrosive effects of geopolitical conflict. Failing to do so ensures that the “elephants” will continue to fight, and the “grass”—the prospects for sustainable development and shared prosperity—will continue to suffer. -

-

The Climate Imperative: The Unavoidable Centre of Gravity in Johannesburg

In the chorus of global crises demanding attention at the G20 summit, one issue resonated with a particular, unignorable urgency: the climate crisis. Framed not as a standalone environmental concern but as an existential threat to economic stability, food security, and global peace, the climate imperative formed the daunting backdrop against all other discussions. In Johannesburg, the debate was no longer about if climate change is real, but about the stark disparity between the escalating impacts and the painfully slow pace of global action. The call from the African host continent was unequivocal: this demands scaled-up, delivered climate finance from developed nations and immediate, actionable decarbonisation plans from all, especially the world’s largest economies.

Africa: The Crucible of Climate Injustice

The summit’s location made the abstract terrifyingly concrete. Africa contributes less than 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions, yet the consequences disproportionately batter its nations. From the devastating drought gripping the Horn of Africa—a crisis pushing millions towards famine—to the tropical cyclones ravaging Southeast Africa with increasing frequency and intensity, the continent is living with the daily reality of a climate crisis it did not create. This inherent injustice framed the entire discussion, transforming it from a technical negotiation into a moral imperative.

For African leaders, the climate crisis is not a future threat; it is a present-day drain on national budgets, a driver of conflict over dwindling resources, and a direct impediment to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. When crops fail due to erratic rains, when coastal cities are threatened by sea-level rise, and when infrastructure is destroyed by extreme weather, the very foundations of economic development are undermined.

The Twin Pillars: Finance and Decarbonisation

The G20’s response to this imperative in Johannesburg coalesced around two non-negotiable pillars:

-

Scaled-Up Climate Finance: The long-standing pledge for developed nations to provide $100 billion annually in climate finance to developing nations has been a source of deep frustration, having been missed for years. In Johannesburg, the demand was not just for this promise to be finally met, but for it to be seen as a floor, not a ceiling. The argument, articulated powerfully by African and other Global South leaders, is that you cannot have a credible decarbonisation plan without a credible financing plan. This finance is not charity; it is reparational and essential for building resilience (adaptation) and enabling a leapfrog to renewable energy (mitigation). The Africa Investment Atlas, while broad, is a tool through which such climate-compatible investments can be tracked and prioritised.

-

Actionable Decarbonisation Plans: There was a palpable impatience with vague net-zero targets set for 2050. The demand was for concrete, near-term roadmaps from the G20’s major emitters. This means clear, legislated plans to phase out fossil fuels, invest in grids and storage, and accelerate the transition to renewables. The tension here lies in the different starting points: developed nations must decarbonise their mature economies, while many African nations rightly demand the policy space to address energy poverty and industrialise, albeit hopefully along a greener path.

The Adage and the Unavoidable Reckoning

The entire discussion around the climate imperative in Johannesburg brought to mind the stark adage, “You reap what you sow.” For centuries, the industrialised nations of the Global North have sown the seeds of their prosperity through a carbon-intensive industrial revolution. The G20, which includes these historical emitters, is now confronted with the global harvest of that sowing: a destabilised climate.

The profound injustice is that Africa is being forced to reap a harvest it did not plant—a harvest of failed seasons, submerged communities, and shattered livelihoods. The call for scaled-up finance is, in this light, a demand for those who sowed the whirlwind to now help others build storm shelters. It is a matter of historical responsibility and intergenerational equity.

The Johannesburg Legacy: A Question of Credibility

Ultimately, the G20’s handling of the climate imperative was a direct test of its credibility. To have convened in a region on the front lines of the crisis and failed to make substantial progress would have been an unforgivable failure. While the summit may not have solved the entire problem, it succeeded in keeping the pressure mounted and framing the issue in the starkest terms yet.

The final communiqué’s language on climate was undoubtedly a compromise, but the very fact that it was underscored as an “existential threat” signals a shift in tone. The challenge now is to move from recognising the adage’s truth to altering its outcome. The world has sown the wind of carbon emissions; the work of the G20 must be to ensure that our collective future is not one of reaping the whirlwind, but of cultivating a sustainable, and just, resilience. The success of this endeavour will be the ultimate measure of the Johannesburg summit’s legacy.

The final communiqué’s language on climate was undoubtedly a compromise, but the very fact that it was underscored as an “existential threat” signals a shift in tone. The challenge now is to move from recognising the adage’s truth to altering its outcome. The world has sown the wind of carbon emissions; the work of the G20 must be to ensure that our collective future is not one of reaping the whirlwind, but of cultivating a sustainable, and just, resilience. The success of this endeavour will be the ultimate measure of the Johannesburg summit’s legacy. -

-

Future-Proofing Health Security: The Unfinished Business of the Pandemic

In the conference rooms of Johannesburg, the ghost of COVID-19 was an uninvited yet ever-present delegate. The memory of overstretched hospitals, shattered economies, and the stark global inequity in vaccine distribution hung heavy in the air. The pandemic served as a brutal, real-world drill, exposing the profound vulnerabilities of a fragmented global health architecture. Consequently, “future-proofing health security” was not a theoretical exercise for the G20 leaders; it was an urgent imperative, necessitating the establishment of robust, co-ordinated global health systems and, critically, equitable funding mechanisms to ensure the world is not caught so catastrophically unprepared again.

The Scarring Legacy of COVID-19 in Africa

For the African continent, hosting this discussion was deeply personal. The pandemic revealed a dangerous dependency on global supply chains for essential medical supplies, from vaccines to personal protective equipment. The phenomenon of “vaccine apartheid,” where wealthy nations hoarded initial doses while low-income nations waited, was a searing lesson in the fragility of international solidarity during a crisis. This experience fundamentally shifted the continent’s priority from mere pandemic response to health security sovereignty.

The discussions in Johannesburg were therefore not just about preventing the next pathogen. They were about rectifying the systemic failures that left Africa at the back of the queue. The goal is to ensure that when the next pandemic strikes—a matter of “when,” not “if”—every continent has the capacity to detect, contain, and combat the threat without having to plead for resources from others.

Building the Pillars of Resilience

The G20’s vision for future-proofing, as articulated in Johannesburg, rests on three interconnected pillars:

-

Robust and Co-ordinated Systems: This means moving beyond ad-hoc crisis response to building permanent, interoperable infrastructure. This includes strengthening the World Health Organization (WHO), but also enhancing regional surveillance networks so that an outbreak in one country triggers an immediate, co-ordinated regional response. For Africa, this aligns directly with the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention’s (Africa CDC) mission to build continental early warning systems and a network of reference laboratories.

-

Equitable Funding Mechanisms: The summit recognised that preparedness is impossible without predictable and substantial funding. The current system of scrambling for funds after a crisis begins is fatal. The focus was on establishing permanent financial pools, such as the World Bank’s Pandemic Fund, but ensuring they are adequately capitalised and accessible to low- and middle-income countries without bureaucratic delay. The principle is that it is far cheaper to fund preparedness than to bail out the global economy during a lockdown.

-

Local Manufacturing and Knowledge Sovereignty: A key outcome, strongly advocated by South Africa and its partners, was the need to decentralise the production of medical countermeasures. This involves transferring vaccine and therapeutic technology to regional hubs in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The mRNA vaccine technology transfer hub in South Africa was cited as a model for the future. This is not just about health; it is about industrial policy, job creation, and strategic autonomy, ensuring life-saving tools can be produced where they are needed most.

The Adage and the Cost of Complacency

The entire endeavour of future-proofing health security is perfectly captured by the adage, “For want of a nail, the kingdom was lost.” The COVID-19 pandemic was a devastating real-life enactment of this proverb. The “nail” was a lack of investment in a single laboratory network or a surveillance system in one region. This led to the “lost horseshoe” of delayed detection, the “lost rider” of an uncontrolled outbreak, the “lost battle” of a global pandemic, and the near “lost kingdom” of a paralysed world economy.

The G20 discussions in Johannesburg were a collective acknowledgment that we cannot afford to lose the kingdom again. Investing in the “nails”—the local community health workers, the regional labs, the manufacturing capacity in the Global South—is not an extravagant cost, but the most essential insurance policy for humanity.

The G20 discussions in Johannesburg were a collective acknowledgment that we cannot afford to lose the kingdom again. Investing in the “nails”—the local community health workers, the regional labs, the manufacturing capacity in the Global South—is not an extravagant cost, but the most essential insurance policy for humanity.Conclusion: A Test of Resolve

The Johannesburg summit made significant strides in placing health security firmly on the G20’s permanent agenda. The challenge, as always, lies in implementation. Pledges must be turned into palpable funds, and co-operation agreements must be translated into vials of vaccines and trained epidemiologists on the ground.

The ghost of COVID-19 served as a powerful motivator. By focusing on equitable systems and local capacity, the G20 has the opportunity to ensure that the next health crisis is a manageable storm, not a civilisation-altering tsunami. The true test will be whether, in the calm between pandemics, the world’s economic leaders retain the political will to finish the job they acknowledged as so critical in Johannesburg. Future-proofing is a continuous process, and the work has only just begun.

-

-

Tackling Energy and Food Instability: The Twin Engines of Global Crisis

In the nuanced calculus of global stability, the G20 summit in Johannesburg placed a stark emphasis on two of the most fundamental human needs: energy and food. Delegates were forced to confront an uncomfortable truth—that widespread energy and food insecurity are not merely humanitarian concerns, but primary drivers of a dangerous, self-reinforcing cycle of inflation, hunger, and political volatility. For the nations of the Global South, and for the African host continent in particular, this is not a theoretical risk but a daily, grinding reality that threatens to undo decades of hard-won developmental progress.

The Vicious Cycle: From the Field to the Fuel Pump

The connection between energy and food is inextricable in the modern globalised economy. The crisis manifests as a vicious, three-part cycle:

-

The Fertiliser and Fuel Link: Modern agriculture is energy-intensive. It relies on synthetic fertilisers, the production of which requires vast amounts of natural gas. It depends on diesel to power tractors for planting and harvesting, and fuel for transportation to get produce to market. When energy prices soar, as they have due to geopolitical conflicts and market volatility, the cost of fertiliser and farm operations skyrockets in tandem.

-

The Supply Shock: The war in Ukraine, a breadbasket nation, violently disrupted global supplies of wheat, sunflower oil, and barley. This created a massive supply shock, pushing global food prices to record levels. For the many African nations that rely on imports from the Black Sea region, this was a direct hit to their food security and national budgets.

-

Inflation and Instability: Soaring food and energy prices are the primary drivers of inflation, especially in developing economies where a larger proportion of household income is spent on these essentials. As the cost of living spirals, it erodes purchasing power, fuels public discontent, and leads to social unrest. We have seen this play out on the streets of several nations, where protests over bread and fuel prices have escalated into political crises, toppling governments and destabilising regions.

The African Crucible

For Africa, this is a crisis of existential proportions. The continent faces a paradox: it is rich in potential renewable energy and arable land, yet it remains profoundly vulnerable to these shocks. Many nations lack the refining capacity to process their own crude oil, forcing them to import expensive refined fuels. Similarly, despite its agricultural potential, underinvestment in infrastructure, storage, and climate-resilient farming techniques leaves the continent susceptible to global price swings.

The human cost is measured in rising malnutrition, particularly among children, and the desperate migration of those who can no longer sustain a livelihood on their land. For the leaders gathered in Johannesburg, the political cost was equally clear: no government can deliver stability and prosperity on an empty stomach.

The human cost is measured in rising malnutrition, particularly among children, and the desperate migration of those who can no longer sustain a livelihood on their land. For the leaders gathered in Johannesburg, the political cost was equally clear: no government can deliver stability and prosperity on an empty stomach.The G20 Response: From Crisis to Strategy

The summit’s response, therefore, had to be structural, not just symptomatic. The final declaration’s mandate to increase food production was a direct rebuttal to protectionist policies that restrict exports and exacerbate shortages. The logic is that in a crisis, the world needs more food in the system, not less.

Concurrently, the drive for a just energy transition took on new urgency. For Africa, this is not solely about switching from fossil fuels to renewables for the sake of the planet; it is about achieving energy sovereignty. Harnessing the continent’s immense solar, wind, and geothermal potential is a strategic imperative to break the cycle of expensive fuel imports, power local industries and agriculture, and build economies that are resilient to global energy price shocks.

The Adage and the Imperative

The entire discussion was underpinned by a sobering adage: “A drowning man cannot drink from an empty well.” This captures the desperation of the situation. The “drowning man” is the citizen of the Global South, battered by the waves of inflation and hunger. The “empty well” represents the current broken system—a system of fragile supply chains, volatile markets, and inadequate local capacity that fails to deliver in a crisis.

The G20’s challenge, articulated forcefully from the African podium, was to fill the well. This means:

-

Investing in localised food systems: Boosting regional fertiliser production, improving grain storage to prevent post-harvest losses, and supporting smallholder farmers with climate-resilient seeds and techniques.

-

Accelerating the energy transition as a development tool: Deploying finance and technology to build mini-grids that power rural agro-processing plants and irrigation systems, thereby increasing food production and energy access simultaneously.

Conclusion: A Foundational Challenge

In Johannesburg, the G20 rightly identified energy and food instability as a foundational challenge. They are the bedrock upon which economic stability and social peace are built. When they crumble, everything else—climate goals, health security, poverty reduction—becomes immeasurably harder to achieve. The summit’s legacy on this front will be judged by its ability to catalyse the investment and co-operation needed to build a world where the well is always full, ensuring that no nation is left drowning in the storms of global volatility.

-

-

The Disparity Divide: The Ticking Time Bomb of Inequality and Youth Idleness

Amid the grand geopolitical and economic dialogues at the G20 summit, a more insidious, slow-burning crisis was pushed to the forefront by the African host nation: the corrosive and widening chasm of inequality and chronic unemployment. This was not presented as a secondary social issue, but as a fundamental, non-negotiable prerequisite for long-term global stability. In a world still grappling with the aftershocks of a pandemic and ongoing conflicts, the leaders in Johannesburg were forced to confront a stark truth—a world of profound disparity is a world perpetually on the brink of fracture.

The African Reality: A Demographic Crucible

Nowhere is this challenge more acute than in Africa, a continent boasting the world’s youngest population. Every year, millions of energetic, ambitious young people enter the job market, full of potential. However, the pervasive lack of formal employment opportunities, coupled with stark inequalities in wealth, education, and access to digital tools, transforms this “demographic dividend” into a potent demographic risk. When a vast, educated, and connected youth cohort finds itself with no legitimate pathway to prosperity, the foundations of social cohesion begin to crumble.

This disparity is not merely economic; it is multidimensional. It is the divide between the urban elite and the rural poor, between those with stable internet access and those without, and between a small, wealthy older generation and a vast, struggling younger one. This fosters a deep sense of marginalisation and injustice, which can be easily exploited by extremist narratives, fuels political instability, and triggers waves of migration as the desperate seek opportunity elsewhere.

This disparity is not merely economic; it is multidimensional. It is the divide between the urban elite and the rural poor, between those with stable internet access and those without, and between a small, wealthy older generation and a vast, struggling younger one. This fosters a deep sense of marginalisation and injustice, which can be easily exploited by extremist narratives, fuels political instability, and triggers waves of migration as the desperate seek opportunity elsewhere.The G20’s Recognition: From Niche Concern to Core Security Issue

The South African presidency successfully reframed inequality and youth unemployment from a domestic policy challenge to a systemic risk to the global economic order. The argument put forward was compellingly simple: there can be no durable macroeconomic stability in a world of microeconomic despair. A nation where the majority of its youth are idle or underemployed does not provide a stable market for trade, a resilient partner for supply chains, or a cooperative actor in the international system.

The discussions highlighted how this divide directly undermines the G20’s own goals:

-

Climate Transition: A just energy transition is impossible if it creates job losses in traditional sectors without offering viable alternatives for the displaced workforce and the incoming youth.

-

Digital Transformation: The benefits of the digital economy are lost if access to technology and the skills to use it are concentrated in the hands of a few, creating a new “digital divide” to mirror the economic one.

-

Health Security: Pandemics disproportionately harm the poor and marginalised, who live in crowded conditions and lack access to quality healthcare, making the entire global population less safe.

The Adage and the Imperative

The urgency of this issue is perfectly encapsulated by the adage, “a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.” For too long, global economic strategies have focused on strengthening the strongest links—the most advanced industries, the most integrated nations. The G20 in Johannesburg served as a powerful reminder that the entire chain of global prosperity is critically vulnerable to the breaking of its weakest links. A generation of disenfranchised youth in the world’s fastest-growing continent is not a weak link; it is a potential point of catastrophic failure for everyone.

From Diagnosis to Prescription: The Johannesburg Response

Recognising the problem was only the first step. The summit’s response coalesced around a few key strategies, deeply influenced by the African context:

-

Education and Skills Revolution: Moving beyond literacy and numeracy to focus on future-proof skills: digital literacy, green technology, and entrepreneurialism.

-

Supporting the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA): Seen as a primary engine for job creation, by creating a single continental market that allows small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to scale up and hire locally.

-

The Africa Investment Atlas: This digital tool is designed not just to track large-scale infrastructure, but also to highlight opportunities in sectors with high job-creation potential for youth, such as agro-processing, creative industries, and renewable energy.

-

Formalising the Informal Economy: A massive share of African youth work in the informal sector. The focus shifted to how investment and policy can help formalise these activities, providing social protection and a path to growth.

Conclusion: The Stability Imperative

The G20’s focus on the disparity divide in Johannesburg was a mature acknowledgment that GDP growth figures are a poor measure of a nation’s health. True, sustainable stability is not grown in a treasury; it is built in the hearts and minds of a nation’s youth. By making this issue non-negotiable, the African host continent delivered one of the summit’s most crucial messages: investing in equity and youth employment is not a cost, but the most critical investment we can make in our collective future. To ignore this is to build a global economy on a foundation of sand, forever at risk of being washed away by the tides of discontent.

-

-

Poverty and Conflict: The Vicious Cycle Undermining Our Common Future

In the refined setting of the G20 summit, leaders were compelled to confront one of the most brutal and intractable realities of our time: the sinister, self-perpetuating relationship between extreme poverty and violent conflict. This was not presented as two separate crises, but as a single, fused threat that systematically dismantles the foundations of sustainable development. In acknowledging this vicious cycle, the Johannesburg gathering recognised that you cannot hope to build lasting prosperity in a world where millions are trapped in a downward spiral of deprivation and violence.

The Anatomy of a Vicious Cycle

The cycle operates with a grim, predictable logic:

-

Poverty Breeds Conflict: Extreme poverty, characterised by a lack of economic opportunity, scarcity of resources, and inadequate access to education, creates a fertile breeding ground for instability. When young people see no future for themselves in the formal economy, they become vulnerable to recruitment by armed groups, criminal syndicates, or extremist organisations that offer a sense of purpose, belonging, and a means of income. Competition over dwindling resources like water and arable land, exacerbated by climate change, frequently escalates into inter-communal violence. As the adage goes, “a hungry man is an angry man.” Widespread hunger and destitution erode social trust in governing institutions, making societies susceptible to collapse and rebellion.

-

Conflict Deepens Poverty: Conversely, when conflict erupts, it acts as an economic neutron bomb, destroying the very assets needed to escape poverty. It decimates critical infrastructure—schools, hospitals, roads, and markets. It disrupts agriculture, leading to famine. It forces millions to flee their homes, becoming internally displaced persons or refugees, severing them from their livelihoods and creating a lost generation of children without education. Conflict also diverts colossal sums of national revenue away from healthcare and development and towards military expenditure, bankrupting states and entrenching deprivation for decades.

The African Context: A Living Laboratory of the Crisis

For the African hosts and delegates, this is not an abstract theory but a daily, lived experience across multiple regions, from the Sahel to the Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes. The summit’s location in Johannesburg forced a stark focus on this issue. Nations like South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Somalia serve as tragic case studies where the cycle has become entrenched, with each round of violence pushing development indicators back by a generation.

The message from the African continent was clear: you cannot discuss macroeconomic stability in boardrooms while the foundations of society are being destroyed in conflict zones fuelled by poverty. Sustainable development—the central mandate of the G20—is a fiction in a war zone. There can be no “resilient growth” when farms are burned, no “digital transformation” when communities lack electricity, and no “health security” when clinics are targeted.

The message from the African continent was clear: you cannot discuss macroeconomic stability in boardrooms while the foundations of society are being destroyed in conflict zones fuelled by poverty. Sustainable development—the central mandate of the G20—is a fiction in a war zone. There can be no “resilient growth” when farms are burned, no “digital transformation” when communities lack electricity, and no “health security” when clinics are targeted.The G20’s Response: A Shift from Symptom to Cause

The Johannesburg discussions represented a critical evolution in thinking. The traditional approach of treating poverty and conflict as separate issues—with development agencies working in siloes from peacekeeping missions—was deemed insufficient. The G20 recognised that breaking the cycle requires an integrated strategy that simultaneously addresses both halves of the problem:

-

Targeted Economic Interventions in Fragile States: This means directing investment and aid not just to stable, well-governed nations, but strategically into regions teetering on the brink of conflict. The proposed Africa Investment Atlas is a tool for this, designed to de-risk and highlight opportunities in non-traditional markets, potentially creating jobs and economic alternatives to violence in volatile regions.

-

Conflict-Sensitive Development: All G20-led initiatives, from climate finance to infrastructure projects, must now be designed with an understanding of local conflict dynamics. Building a road can either connect marginalised communities to markets (reducing poverty and tension) or it can become a resource for militias to control (escalating conflict). The approach must be nuanced and intelligent.

-

Strengthening Governance: A key insight is that the space between poverty and conflict is often filled by weak governance. Therefore, supporting transparent institutions, the rule of law, and anti-corruption measures is a direct investment in breaking the cycle. It ensures that economic opportunities are perceived as fair and that grievances can be addressed peacefully.

Conclusion: Breaking the Chain

The G20’s acknowledgement of the poverty-conflict nexus in Johannesburg was a moment of profound clarity. It underscored that the most significant impediments to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development are not technical or financial, but political and security-related. The adage “a hungry man is an angry man” serves as a timeless warning of the individual’s reaction to despair. When multiplied across millions, it becomes a blueprint for systemic collapse.

The summit’s legacy on this front will be determined by its ability to catalyse a new form of co-operation—one where diplomats, development experts, and security officials work in concert. To break this vicious cycle is to perform the most vital surgery on the global body politic, removing a cancerous tumour that has for too long metastasised, consuming hope and stability in its path. It is the ultimate test of whether the collective will of the world’s largest economies can be harnessed not just for growth, but for peace itself.

-

-

Stability as the New Currency: The Foundational Lesson from Johannesburg

Amid the complex policy debates and ambitious initiatives that defined the G20 summit in Johannesburg, a singular, powerful consensus crystallised, cutting through the noise with the clarity of a balance sheet: demonstrable political and economic stability is the most valuable asset a nation can possess in the 21st century. This was not presented as a vague aspiration, but as a core, actionable policy position—the fundamental prerequisite for progress. In the global marketplace, stability has quite simply become the new currency, and it is the primary determinant of whether investment, the lifeblood of development, flows in or out.

The Investor’s Calculus: Beyond the Resource Curse

For decades, the narrative around investment in Africa was often narrowly focused on its vast natural resources—its oil, minerals, and gas. The Johannesburg summit marked a decisive shift from this “resource curse” mentality to a more sophisticated understanding of the “stability premium.” International capital, whether from private equity firms, multinational corporations, or development finance institutions, is inherently risk-averse. It seeks not just high returns, but predictable returns.

This investor calculus weighs several factors that fall under the umbrella of stability:

-

Political Stability: Predictable governance, the rule of law, and the absence of violent conflict or sudden, arbitrary policy shifts.

-

Economic Stability: Sound fiscal management, controlled inflation, and transparent financial systems.

-

Social Stability: Cohesive societies, educated workforces, and the absence of widespread civil unrest.

Where these elements are present, investment follows. Where they are absent, even the most resource-rich nation will struggle to attract the capital necessary to unlock those very resources.

The African Context: From Perception to Performance

The setting of the summit in South Africa’s commercial hub was a living testament to this principle. The continent has long battled a perception of instability, often overshadowing its many success stories. The G20 dialogue, steered by African leaders, was a powerful exercise in rebranding. The argument was clear: for every headline about conflict, there are multiple nations demonstrating remarkable resilience, democratic consolidation, and economic reform.

The focus on stability is, for Africa, a pragmatic and empowering reframing. It places the agency for development squarely in the hands of national and continental institutions. It suggests that the path to prosperity is not solely dependent on fickle international aid, but on the deliberate, internal work of building robust institutions, fighting corruption, and fostering social cohesion. This creates a virtuous cycle: stability attracts investment, which creates jobs and economic growth, which in turn reinforces stability.

The focus on stability is, for Africa, a pragmatic and empowering reframing. It places the agency for development squarely in the hands of national and continental institutions. It suggests that the path to prosperity is not solely dependent on fickle international aid, but on the deliberate, internal work of building robust institutions, fighting corruption, and fostering social cohesion. This creates a virtuous cycle: stability attracts investment, which creates jobs and economic growth, which in turn reinforces stability.The Adage and the Virtuous Cycle

This entire philosophy is perfectly captured by the adage, “nothing succeeds like success.” A nation that demonstrates a commitment to stability creates a self-reinforcing positive feedback loop. An initial success in, for instance, conducting peaceful elections or taming inflation, builds confidence. This confidence attracts a first wave of investment, perhaps in a infrastructure project or a manufacturing plant. The success of that project then serves as a tangible proof point, a beacon that attracts further, larger investments. The nation’s reputation for stability grows, its “currency” appreciates, and the cycle of success builds upon itself. Conversely, a nation trapped in a cycle of instability finds the opposite to be true—failure begets further failure, and capital flees.

The G20’s Role: Underwriting the New Currency

The G20’s recognition of this dynamic in Johannesburg was crucial. It moved the forum’s focus from merely reacting to crises to proactively building the foundations of stability. This is the strategic rationale behind initiatives like the Africa Investment Atlas. By creating a transparent digital platform to track investment and policy reforms, the G20 is not just providing a tool; it is helping to de-risk the African continent in the eyes of global capital. It is providing the verified data and transparency that investors need to confidently convert their funds into the “stability currency” offered by reforming nations.

Furthermore, the G20’s commitment to supporting climate-resilient infrastructure, food security, and pandemic preparedness are all, at their core, investments in stability. A farmer whose crops are resilient to drought is an agent of economic and social stability. A community with a reliable health clinic is a bulwark against the instability that pandemics unleash.

Conclusion: The Ultimate Dividend

The conclusion from the Sandton Convention Centre was unequivocal. In a world of polycrises, stability is no longer a passive condition; it is an active, strategic pursuit. It is the bedrock upon which all other development goals—from education and health to climate action and industrialisation—are built. By enshrining stability as a core policy goal, the G20 acknowledged a fundamental truth: the most valuable dividend for any nation is not a short-term boom, but the long-term, compound interest of peace, predictability, and good governance. For Africa, and for the world, the message is that the surest path to a prosperous future is to become a safe bet.

-

-

The Three-Pronged Resilience Strategy: A Blueprint for a Shock-Proof World

In the face of the convergent crises that dominated the G20 agenda in Johannesburg, a clear and pragmatic blueprint for action emerged. Leaders acknowledged that the era of simply reacting to global shocks is over; the new imperative is to proactively build systemic resilience. This is not a single policy, but a holistic strategy, agreed upon as the only viable path forward, resting on three interdependent pillars: inclusive economic growth, shared responsibility, and sustainable development. Together, they form a tripod of stability—remove one leg, and the entire structure collapses.

1. Inclusive Economic Growth: The Bedrock of Social Cohesion

The first pillar represents a decisive move away from the trickle-down economics of the past. “Inclusive growth” recognises that an economy which only benefits a narrow elite is inherently fragile. Social unrest, political polarisation, and a disenfranchised populace are the predictable outcomes of such disparity, making any society vulnerable to internal and external shocks.

In the African context, this means economies must be structured to absorb the continent’s burgeoning youth population into formal, dignified work. It necessitates supporting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which are the largest employers in most African nations. It demands empowering women and marginalised communities to fully participate in the economy. The Africa Investment Atlas, championed at the summit, is a tool for this very purpose: by directing transparent capital towards job-creating sectors like manufacturing and digital infrastructure, it aims to ensure that the benefits of growth are broadly shared, creating a more stable and cohesive society.

2. Shared Responsibility: The Cornerstone of Global Solidarity

The second pillar, “shared responsibility,” is a direct rebuttal to the isolationist and “every nation for itself” mentality that has weakened the global response to recent crises. It acknowledges that in an interconnected world, vulnerabilities anywhere are threats everywhere. A pandemic originating in one continent can shut down the global economy. Carbon emissions from industrialised nations can cause droughts that trigger famine in another.

For the G20, this means the historical emitters must take greater responsibility for financing the green transition. It means that wealthy nations, which hoarded vaccines during COVID-19, must help build pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity in Africa to ensure health security for all. This principle transforms global challenges from a burden to be shifted into a common mission to be shouldered collectively. It is the understanding that building a resilient health system in West Africa or a climate-resilient agricultural sector in the Horn of Africa is not charity, but a vital investment in global stability.

3. Sustainable Development: The Guarantor of Long-Term Viability

The third pillar binds the strategy together in both time and scope. “Sustainable development” insists that we cannot solve today’s poverty by creating tomorrow’s ecological catastrophe. Resilience cannot be built on the rapid depletion of natural resources or on carbon-intensive growth that exacerbates the climate crisis.